The importance of video games to human development cannot be overstated. I believe there have been three major inventions that have radically expanded the human species and the reality we continue to create for ourselves. The first would be movable type and the advent of the printed word, the second would be motion pictures, and the latest revolutionary intellectual force would be interactivity. Video games and the internet that many of them run on has irreversibly transformed the human race and set our consciousness on an exciting new course of development.

The importance of video games to human development cannot be overstated. I believe there have been three major inventions that have radically expanded the human species and the reality we continue to create for ourselves. The first would be movable type and the advent of the printed word, the second would be motion pictures, and the latest revolutionary intellectual force would be interactivity. Video games and the internet that many of them run on has irreversibly transformed the human race and set our consciousness on an exciting new course of development.I marvel at the advancements this medium has displayed in my lifetime. From photo realistic graphics to complex game mechanics to real world physics we are seeing video games mature and match sophistication with the other, older mediums in a relatively short period of time. I feel however that in one particular area video games are stagnating, shockingly and perplexingly so.

Not nearly enough games are telling us stories worth paying attention to.

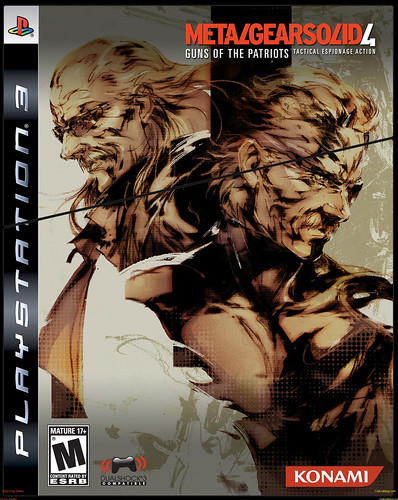

These personal thoughts have coalesced into this essay over the past few months where I have played some of the most technically impressive games of my life, all the while having to suffer through some terribly ineffective stories. The magnum opus that is Grand Theft Auto IV is really just a thin tale of crime and retribution made even cheaper by how much material it shamelessly lifts from other sources such as The Wire. The latest Metal Gear Solid is even worse; a melodramatic abortion without subtlety or restraint. You may disagree with my two examples and of course that’s fine. To make my point I instead ask you to look over your own collection of games and take note of the many worthwhile titles where the narrative runs from poor to just plain awful. More often than not, story is the weakest part of any game. Resident Evil 4, Gears of War, Army of Two, Dark Sector, Devil May Cry 4, Halo 3, and Condemned 2 are titles I’ve recently played or replayed that easily come to mind. I loved the game play in each of these titles but the story in all of them was very poorly imparted. There were interesting concepts and imaginative scenes but the good writing needed to thread them all together was absent.

Good writing can and does take place, which is why the culture of narrative failure present in the video game industry is all the more mystifying. Epic, far-reaching stories have been effectively told in this medium. As recent examples I thought Mass Effect, Bioshock, and the Half-Life episodes did a fine job, at least fine enough given the overall ineptitude of their peers. Small, contained and compelling stories have also been told. In Portal we have the simple arc of a malfunctioning A.I. who hopes to lure a test subject to their doom only to be outwitted and destroyed… That and cake. Portal exemplifies the fact that it’s not what story you’re telling but how you tell it. How come so many video game developers don’t know how to tell their own stories?

Being an avid game consumer but admittedly looking from the outside – in, I have come to speculate on why effective storytelling seems so vexing to game development. Just as movie writing isn’t the same as book writing, is there some radical, hereto forth yet to be discovered skill-set needed to create the video game equivalent of a page-turner? Has the industry not committed to the writing process as they have to coding or animation? Are video games inherently at cross purposes with story telling and only rare geniuses can occasionally skirt this inevitability? Perhaps each major development house has a different answer to my question but what I can say with absolute certainly is that we, the players, should be taking some of the blame.

We accept these stories, you see. We pay, we play, we praise, and all the while we remain mostly silent on the quality of the narrative. We are silent because we have accepted that poor storytelling is the norm. We tell ourselves that the medium is still in its infancy, or that the luminary artists of literature have not yet embraced games as a career path, or that story is naturally going to take the back seat to a product that allows you to shoot people in the head for hours on end. We make excuses for the developers who in turn fail to consider story as a priority. They are not motivated to evolve.

We should demand they evolve!

If a story goes nowhere, falls flat, is uninteresting, has been told too many times, or is just preposterously stupid then it should be pointed out, emphatically. The enthusiast media’s ranking system leaves much to be desired and has been rightly vilified as of late, yet it is the only system we have and it should be made to take the writing more into account. If a game comes with an idiotic or half-assed story it should be mentioned and a perfect or near perfect score should be out of reach.

Our personal criticisms should always be constructive of course, but they should be vocal enough so that they are taken to heart by the game creators. By the same token if a game tells a fine story it should be encouraged, even if the other aspects of the game are not up to snuff. After all, isn’t turnabout fair play? For too long we have accepted awful writing because the visuals and game play are excellent.

We should be putting the writing up to the same kind of scrutiny we give the screenshots and trailers. Dedicated game players no longer accept poor quality graphics and surprise; the vast majority of games these days look beautiful, I dare say even excessively so. We the players can and have affected the culture of gaming on a wide variety of issues - for both good and ill depending on who you ask. Now we need to begin a new groundswell to bring the writing proficiency in step with the other, more advanced aspects of game design.

Video game industry to exceed 68 Billion dollars by 2012.

Last year the industry made over 40 Billion in revenue, double what it earn just five short years ago. The industry is massive and seems to be growing at an incredible rate.

.

No comments:

Post a Comment